Dune, Survivor Bias and the National Student Survey

At the time of writing Dune Part Two has just been released in cinemas. The film is of course based on the 1965 book Dune, which has many fascinating themes. One of these is around what makes the Sardaukar - the troops of the Padishah Emperor the second most élite soldiers of the known universe, and [mild spoilers if you didn't read the book or see Dune Part One], what makes the truly native people of Arrakis, the Fremen, the most élite soldiers of the known universe.

The Sardaukar and specifically their origin is, at the start the book, shrouded in mystery. They are regarded with fear by the Great Houses who struggle to produce such effective fighting forces, or at least in such numbers. The Sardaukar themselves seem to have a fanaticism that is unmatched. As the book progresses, we learn a secret. The Sardaukar are the product of the Emperor's Prison Planet - Salusa Secundus. This ruthlessly brutal environment resulted in a devestating mortality rate - but strangely - through a Stockholm Syndrome like alchemy the survivors developed a semi mystical religous fervour, a spirit of brotherhood and a fanatical loyalty to the Emperor - despite him being responsible for their upbringing in hellish conditions.

Survivor Bias

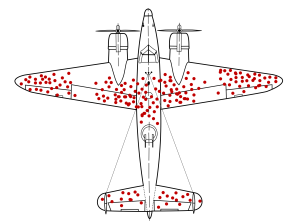

If you have heard of Survivor Bias before, you may already have seen a version of this very famous image. In World War II an effort was undertaken to understand how to armour bombers more effectively against being shot down. An analysis was conducted as to where the bullet holes were found in returning aircraft, and it seemed obvious that these areas required reinforcement.

The statistician Abraham Wald realised that was completely missing the point. The only data available was for returning planes, but it was precisely the data on the non returning planes - those that had been shot down - that was needed. After all, the returning planes had survived being shot on the areas with the red dots, and so it is precisely those areas with an absence of red dots where we should be paying attention. It's entirely reasonable to assume that the planes were being shot in those areas too, but those hits were the critical ones.

In other words, one of the lessons of Survivor Bias is we have to pay careful attention to the question of what data is simply invisible, but which actually must be the most critical.

What has this got to do with Higher Education?

In the UK full time undergraduate students undertake a survey at the last stage of their study - the National Student Survey (NSS). The survey explores many aspects of the student experience, including an overall satisfaction. The interesting thing happens when you compare the correlation of NSS scores with other key higher education metrics - for instance retention and progression.

I have seen examples where, as you would expect, very high NSS scores, especially in overall satisfaction, occur in provision with very solid learning and teaching metrics at all parts of the student journey. So far, so unsurprising. But sometimes you see provision with consistently high overall NSS student satisfaction and consistently poor retention and progression, perhaps with other indicators of poor student satisfaction at early stages of the student journey.

What can we make of such anomalies? My potential working theory is that these are a result of a mixture of survivor bias and a particular form of cohort identity that emerges from difficult conditions. As the NSS is only delivered in the final year of study, we don't really know what responses would have been made by the students who never made it that far - they are the planes that never returned.

The Implications for Universal Design for Learning

Normally, as educators, we are very committed to encouraging a strong cohort identity. But are there circumstances when a strong cohort identity can be a bad thing? While a strong cohort identity can always bring benefits, it can be also be problematic when it's based on a lack of inclusivity, or a feeling of fellowship caused by collective trauma.

In particular, if we have a cohort of students at final year, who having survived high attrition in early years, they may come to see themselves, with some satisfaction as an élite group, and derive a significantly elevated self confidence from their survival. It's not hard to find some academics that see only the benefits in this - after all the Sardauker we talked about at the start really are élite as a result of their harsh surroundings. But we should ask what may have been lost along the way. In our case, these are literal students that didn't make it to the end of study - is that because they couldn't succeed, or because they didn't fit our narrow expectations of what success looks like? And what other, wider definition of élite might have been inculcated into our students in a more inclusive environment, as Universal Design for Learning suggests?

In summary, should we be worried about high NSS results. Well no, it's still wonderful to see students express strong satisfaction in their courses, and we should be data-led in our interventions. But it's always worth asking the question "What is this data not showing us?".